|

| Bagot of Blithfield, Barons Bagot |

The Bagots of Blithfield are in all probability one of the very few families who have held their lands in essentially unbroken continuity since the reign of William the Conqueror, when their core estate of Bagot's Bromley was held by one Bagod of Robert de Stafford. At the beginning of the 19th century the 2nd Lord Bagot, who was an enthusiastic and painstaking antiquary, published his Memorials of the Bagot family, 1824, in which he assembled the evidence for his family's descent in the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries. Despite his care, the availability of a wider range of sources now enables us to detect some inaccuracies in his work, and there are, as always with early medieval genealogy, some gaps in the record which lead to uncertainties. We come onto firmer ground with Sir Ralph Bagot (d. c.1376), who married - probably as his second wife - the heiress of the neighbouring Blithfield estate. Their descendants merged the two estates but lived at Blithfield, and by the early 19th century nothing was left of Bagot's Bromley; the site was marked by the antiquarian Lord Bagot with an inscribed stone, so that it did not pass wholly out of memory.

|

| A drawing of the monument erected on the site of Bagot's Bromley by Lord Bagot in 1811. Image: William Salt Library SV-II.80b (45/7685) |

Richard's son, John Bagot (c.1436-90) survived his father by only a few years, but in the next generation Sir Lewis Bagot (c.1461-1534) had a glittering career in royal service with both King Henry VII and his son, culminating in his accompanying Henry VIII to the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520. Sir Lewis is said to have been married five times (although only four wives seem to be documented, and the first was a child bride whose marriage may never have been consummated), and he is said to have had nineteen children by the second and third wives (although again, only thirteen have left a trace in the records). The eldest surviving son and heir, Thomas Bagot (c.1500-41) was at the helm during the dissolution of the monasteries. There does not seem to be any evidence that he was a purchaser of monastic lands (though his brother Stephen was), and it is not clear what he thought of the religious reforms of the 16th century. His son, Richard Bagot (c.1530-97) was, however, clearly a convinced Protestant: as a JP he was active in enforcing measures against Roman Catholics and he earned the thanks of the Privy Council for his support of those entrusted with the person of Mary Queen of Scots while she was imprisoned in Staffordshire in 1585-86. Richard was the first of his family to exhibit an interest in antiquarian matters, and this no doubt informed the decisions he made about remodelling and enlarging the house at Blithfield, which probably completed its development into a substantial courtyard house in his lifetime. His enthuasism for antiquarian pursuits seems to have overriden political considerations, since it led him into friendly collaboration with the prominent recusant, Sampson Erdeswick (d. 1603) of Sandon Hall. His son, Walter Bagot (1557-1623), was married to a niece of Lord Burghley, and this gave him more influence at court than would normally have been the lot of a country squire. In 1599, Walter's attempt to be excused from serving as sheriff brought him an unexpected and probably unwelcome testimonial from the Queen, who ‘heard he was an honest man like his father, and therefore was sorry she had spared him so long’.

When Walter Bagot died in 1623, his son and heir, Sir Hervey Bagot (1591-1660), who purchased a baronetcy in 1627, was living at Field Hall, Leigh (Staffs). He chose not to move into Blithfield, which his widowed mother continued to occupy until her death in 1638, after which he installed his own heir, Sir Edward Bagot (1616-73), 2nd bt., in the house. During the Civil War, Sir Hervey and his younger sons were active supporters of the Royalist cause, and Col. Richard Bagot (1618-45) died from wounds received at the battle of Naseby. The Blithfield estate was sequestered, and although Lady Bagot recovered possession of Field Hall in 1644, Sir Hervey seems to have lived mainly in the close at Lichfield (when he was not with the King at Oxford) until hostilities ended. Sir Hervey was then allowed to compound for his estates, but as he had been such a prominent delinquent, he faced a swingeing fine. This was paid by his son, Sir Edward, who sold the lands in Buckinghamshire which had come to him through his marriage in 1641. Sir Hervey lived to see the Restoration in 1660, but died shortly afterwards.

Sir Edward Bagot (1616-73), 2nd bt., did not play a discernible part in the Civil War, but it is not clear whether he differed in view from his father's firm support of the Royalist cause or whether this was a tactical matter. He was certainly not active on the Parliamentarian side, although he did become a JP for Staffordshire under the Cromwellian regime in the later 1650s. At the Restoration, his career was no doubt helped by his friendship with Lord Clarendon as well as the record of his family. His brother, Col. Hervey Bagot (1617-74), who had been deputy commander of the Royalist garrison at Lichfield at a tender age, married the heiress of the Arden family and through her acquired Pype Hayes Hall, which remained the property of the family until the early 20th century. Sir Edward himself had no less than seventeen children, and was succeeded in 1673 by the eldest surviving son, Sir Walter Bagot (1645-1705), 3rd bt. Sir Walter seems to have had antiquarian interests like several other members of the family, and was a financial supporter of Dr. Robert Plot's Natural History of Staffordshire, 1686, to which he donated an engraved view of Blithfield. He was also a long-serving MP for the county, although in his later years he was prevented from attending regularly by illness. In 1670 he took as his bride Jane Salusbury, an heiress who had come into the Bachymbyd and Pool Park estates in Denbighshire and Merionethshire, amounting to some 20,000 acres, on the death of her father in 1666. These estates passed into the Bagot family, although Sir Walter had to undertake a spirited defence of his title in the courts in the 1670s. The acquisition doubled the wealth and income of the Bagots, and made them one of the leading Staffordshire county families.

Sir Walter was succeeded by his son, Sir Edward Bagot (1674-1712), 4th bt., who became disabled by gout soon after inheriting the estate and died young, aged just 38. His heir was his son, Sir Walter Wagstaffe Bagot (1702-68), 5th bt., who pursued a remarkably full and rewarding life. He was an MP (of Tory and indeed Jacobite views) for forty-four years, ending up as the representative for the demanding constituency of Oxford University. He had a wide range of artistic, cultural and intellectual interests, which are reflected in his surviving correspondence, his building activities at Blithfield, and the award of an honorary doctorate from Oxford in 1737; and he was involved in a number of charitable projects, including being a trustee of the Foundling Hospital in London and the Radcliffe Library in Oxford. At home, he was married for over forty years to Lady Barbara Legge, daughter of the 1st Earl of Dartmouth, and by her had sixteen children, many of whom also led interesting and fulfilling lives. His eldest son, Sir William Bagot (1729-98), 6th bt., who seems to have shared many of his father's interests, and who, as a consistent promoter of artistic talent, furthered the careers of James Wyatt and Josiah Wedgwood among others, continued the family's parliamentary tradition, and when he retired from the House of Commons in 1780 was raised to the peerage as 1st Baron Bagot. The second son, Charles Bagot (1730-93) was a wine merchant in Oporto (Portugal) until 1755, when he inherited Chicheley Hall (Bucks) from his cousin, Sir Charles Bagot Chester, 7th bt., who passed over several closer relatives in order to make Charles his heir. [An account of his descendants and of Chicheley Hall will be given in a future post on the Chester family]. The third son, Rev. Walter Bagot (1731-1806), inherited Pype Hayes Hall in 1775 on the death of the last of Col. Hervey Bagot's descendants. Both he and his brother Charles were friends of the poet William Cowper, and several of his children evinced intellectual and/or literary interests. Pype Hayes remained the property of his descendants until 1906. The fourth son, Richard Bagot (1733-1818), trained as a lawyer, but in 1761-63 seized the opportunity of a diplomatic mission led by his friend, the Earl of Northampton, to go to Italy, and took with him (perhaps at the suggestion of his elder brother, Sir William) the 16-year-old aspiring architect James Wyatt, whose family came from near Blithfield. Richard left marriage late, but in 1783 married the heiress Frances Howard, who had just inherited Ashtead Park (Surrey) from her uncle and who in 1803 succeeded her mother in an extensive estate including Levens Hall (Westmld), Elford Hall (Staffs) and Castle Rising (Norfk). He took the name Howard in lieu of Bagot, and in 1808 he added to his property portfolio the Fisherwick estate in Staffordshire, which adjoined Elford. All this property subsequently descended to his only daughter, Mary Howard (1785-1877), who remained single throughout her long life, and at her death divided her estates between several distant relatives. [See my forthcoming post on the Bagots of Levens Hall].

|

| Bishop's Palace, St. Asaph: probably designed by Samuel Wyatt for the Rt. Rev. Lewis Bagot |

The 1st Lord Bagot had a somewhat smaller family than his father (only ten children, of whom several died young from scarlet fever), but once again they included several who pursued careers of interest. His second surviving son, Sir Charles Bagot (1781-1843), kt., became one of Britain's first professional diplomats, and ended up as Governor-General of Canada, while his third surviving son, Richard Bagot (1782-1854), entered the church and became a rather reluctant Bishop, forced to confront the crisis in the direction of the church raised by the Tractarian movement. The 1st Baron's heir, however, was William Bagot (1773-1856), 2nd Baron Bagot. He had wide-ranging intellectual interests, was the third successive owner of Blithfield to receive an honorary doctorate from Oxford, and was a Fellow of four learned societies, but unlike his predecessors did not take an active part in politics. He devoted his time instead to antiquarian pursuits, especially the history of his own family, and as we have seen published Memorials of the family of Bagot in 1824. He went beyond celebrating his family history in print, however, to do so in bricks and mortar. At Blithfield he evolved with the artist and architect John Buckler a scheme of remodelling which preserved much of the old fabric of the house, but made it far more picturesquely Gothic than it had been before. At Pool Park he undertook a straightforward rebuilding which no doubt was intended to have a similarly archaic effect, but which to modern eyes is clamantly of its period.

After three generations in which intellectual abilities and interests were unusually apparent, the 2nd Baron's heir, William Bagot (1811-87), 3rd Baron Bagot, cuts a more conventional and less intriguing figure. Although he undertook some European travel in his 20s and was an MP for Denbighshire before he inherited the peerage, it was for his career in the Staffordshire Yeomanry (which he commanded from 1854) and for his dedication to hunting that he was most remarked by his contemporaries. Similar interests are apparent in his son and heir, William Bagot (1857-1932), 4th Baron Bagot. He married an American Roman Catholic in 1903, and the couple produced an only daughter before separating soon afterwards. This left as his heir presumptive a nephew, who was killed in the First World War. The next heirs were two great-grandsons of the 1st Baron, who until 1916 can have had no expectation of inheritance. The elder of them died shortly before the 4th Baron, and the family lawyers experienced some difficulty in tracing the other, who after years training polo ponies in South America was eventually found rather nearer to hand, training racehorses outside Paris. Against this background, and given the successive shocks delivered by the agricultural depression, the rise of redistributive taxation, and the First and Second World Wars, it is perhaps no surprise to find that the sands of the family ran out so quickly in the early 20th century. In 1883, the family still owned 30,543 acres in Staffordshire, Denbighshire and Merionethshire, with a rental of over £22,000 a year, although the mansion at Pool Park was already let. The majority of the North Wales estate was sold in 1928, although Pool Park itself was retained until 1936. The 4th and 5th Barons continued to live at Blithfield, but on an ever more circumscribed basis. By 1943, the 5th Baron was said to be living in three rooms out of 82, looked after by a skeleton staff. It is therefore no wonder that he acceded to a request from the South Staffordshire Water Company to buy the Blithfield estate in 1945. The company wished to create a new water supply reservoir for Birmingham and the Black Country by damming the River Blythe and flooding much of the estate. They specified no plans for the house, and it seems likely that it would have been left empty and demolished in the 1950s like so many others, if matters had proceeded as intended.

The 3rd Baron, at his death, had transferred the ownership of the estate to Trustees, under whom the 5th Baron had something of the position of a life tenant, entitled to the income from the estate. Under the terms of the Trust, however, he did have power to direct the sale of the freehold and contents of Blithfield, but the proceeds of such sales accrued to the Trust and not directly to him personally. He also needed the agreement of the next heir to sell those contents which had been designated as heirlooms. To secure this consent, the 5th Baron invited down the heir presumptive, his second cousin, Caryl Ernest Bagot (1877-1961), 6th Baron Bagot, and his young Australian second wife, Nancy. Recognising that there would be little space in their London home for heirlooms from Blithfield, they set aside a few things they would like to have, and agreed to the sale of the remainder. The contents sales took place in 1945, but the sale of the freehold to the Water Company was still in progress when the 5th Baron died. The new Lord Bagot and his wife came down to Blithfield to clear out the remaining contents and found that they had fallen in love with the place. Although it was too late to stop the sale to the Water Company going through, they persuaded the Will Trustees to buy back the house and some 300 acres of the estate that were not going to be drowned by the Water Company's reservoir, and they began the process of restoring the old house, which was also opened to the public for a time to help raise money for restoration. In 1961, Lady Bagot bought the freehold of the estate from the Will Trust, thus ensuring that when her husband died later that year, the property did not pass with the title to the 7th Baron Bagot, who was again a distant cousin with little connection to the estate, but remained in her possession, allowing her to continue her restoration project. In the 1980s, two wings of the house were sold to provide further funds for restoration and make the task more manageable, and in 1999 Lady Bagot made over the core of the house to a new trust, of which the 6th Baron's great-nephew, Cdr. Charles James Bagot Jewitt (b. 1966), is the present beneficiary. In 2011, Lady Bagot published her memoir, Blithfield House - a country house saved, which provides a detailed account of the advances and reverses by which her heroic rescue of Blithfield proceeded; she died in 2014.

Blithfield Hall, Staffordshire

Blithfield is a low rambling picturesque courtyard house that has developed its present form over several centuries. In medieval times the house occupied a moated platform, the size and shape of which are probably fairly well indicated by the external walls of the house. Part of the moat remained open until c.1769, when it was filled in to allow the addition of a new drawing room at the south-west corner.

The house that came to the Bagots in the mid 14th century was rebuilt soon afterwards, for in 1398, Sir John Bagot complained that Robert Stanlowe, the carpenter, had worked so negligently and unskillfully that it had fallen into ruin. The house then consisted of a hall (probably on the site of the current great hall in the north range), perhaps with cross-wings, and a gatehouse which it may be conjectured stood in the middle of the south range, where the later porch tower is now.

|

| Blithfield Hall: artist's reconstruction of the 16th century hall, viewed from the dais end. Image: South Staffordshire Archaeological & Historical Society. |

Piecemeal alterations and improvements probably continued throughout the 17th century, but the only surviving evidence of these today are the late 17th century panelled study and the main staircase of c.1660-70. This stood originally at the screens end of the hall, but was later moved to its present position in the north range and rearranged.

|

| Blithfield Hall: the staircase of c.1660-70 was moved to its present location in the 19th century. Image: Nicholas Kingsley. Some rights reserved. |

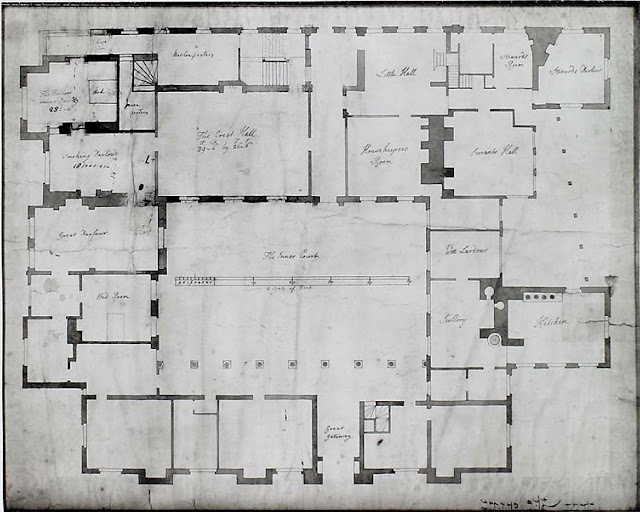

The earliest large-scale remodelling of which anything is known was carried out in c.1738-45 by Richard Trubshaw and his son Charles Cope Trubshaw for Sir Walter Wagstaffe Bagot, 5th bt. This involved adding an additional thin range of buildings to the north front of the house, making the north range into a double-pile. As thus remodelled, the range originally had an austerely plain fifteen bay two-storey facade, although the fenestration was not entirely regular. The elevation has, however, been truncated at both ends by later alterations, so there are today only eleven bays. Also of this time is the decoration of the library on the first floor of the east range, with pilastered panelling.

|

| Blithfield Hall: north and west fronts drawn by John Buckler, c.1828, after his alterations. Image: British Library |

|

| Blithfield Hall: survey plan of the house, c.1740, showing the alterations made by the Trubshaws to the north front. North front at the top. Image: Historic England |

|

| Blithfield Hall: orangery by Athenian Stuart in 1993, before restoration. Image: Nicholas Kingsley. Some rights reserved. |

In 1768 Sir William Bagot (later the 1st Baron Bagot) succeeded his father at Blithfield, and he at once brought in James 'Athenian' Stuart to make improvements to the house. Stuart first designed a fine eleven-bay orangery with pedimented ends facing the north front of the house, the construction of which was entrusted to Samuel and Joseph Wyatt, two young members of an established local building dynasty, whose careers the family had been fostering for some time. Stuart then made proposals for rebuilding parts of the house, but Sir William found his ideas too ambitious, and turned to Samuel Wyatt for less expensive changes.

|

| Blithfield Hall: engraving of the house showing the Samuel Wyatt drawing room at the south-west angle of the house. |

The 2nd Baron Bagot (1778-1856), who inherited Blithfield at the age of 20 in 1798, was both a romantic and an antiquarian, like so many of his generation. He was inspired by the long association of his family with Blithfield to make the house more clamantly medieval than it had ever been before, and in c.1818-24 he planned a major remodelling to this effect. The designs almost certainly came from John Buckler (1770-1851), an assiduous topographical artist and occasional architect, who was later commissioned by Lord Bagot and William Salt of Stafford to make record drawings of Blithfield, and to rebuild Lord Bagot's seat in North Wales, Pool Park.

|

| Blithfield Hall: drawing of the south front as remodelled by John Buckler, c.1820-28. Image: British Library |

|

| Blithfield Hall: the central courtyard, with the Great Hall windows on the right, and the 'cloister' of the 1820s on the left. |

|

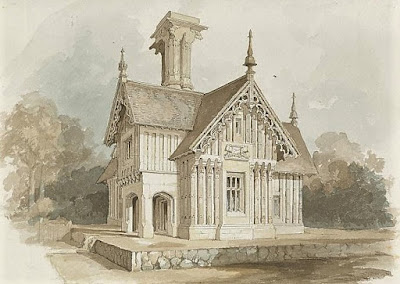

| Blithfield Hall: Goat Lodge: drawing of 1842 by T.P. Wood. Image: William Salt Library/Staffordshire Record Office. |

|

| Blithfield Hall: the plasterwork decoration of the Great Hall in the mid 20th century. |

|

| Blithfield Hall: the plaster ceiling of the Great Hall which now conceals the 16th century timber ceiling illustrated above. Image: Nicholas Kingsley. Some rights reserved. |

|

| Blithfield Hall: an early Victorian watercolour of the interior of the conservatory created by John Buckler in the 1820s. Image: Nicholas Kingsley. Some rights reserved. |

The later 19th century saw few changes at Blithfield. The 3rd Baron brought in William Burn in 1860 to carry out some minor works, and later also consulted George Devey on at least three occasions (in 1866, 1873 and 1882). A game larder was built north-east of the house in 1895. But like so many families, the Bagots found they were increasingly hard up in the last quarter of the 19th century and the early 20th century. The 5th Baron, who inherited in 1932 at the age of sixty-six, occupied only a fraction of the house before the Second World War and by 1943 a distant relative visiting for the first time recorded 'Blithfield could come straight out of a book about someone going to a haunted castle that has been asleep for seventy years - as it has been... [Lord Bagot] lives in three rooms out of eighty-two, and is a lonely, but charming, old man... He took me all over the house, which must be one of the most complete museums in existence'. Within two years, however, Lord Bagot had contracted to sell the estate to the South Staffordshire Water Works, who wished to make a reservoir in the park, and held a grand sale (in 1945) of the contents of the house. He died the following year, leaving the title and estate to his cousin, Sir Caryl Bagot (1877-1961), 6th Baron Bagot. The sale to the water company was then too far advanced to be stopped, but when the 6th Baron and his much younger Australian wife visited the house to pack up the remaining contents, they fell in love with the place. They succeeded in getting the family trust to buy back from the Water Company the house and 300 acres, and over the next fifteen years invested all their time and energy in modernising and improving the condition of the house, which was also opened to the public. From 1953 onwards they restored and redecorated with the advice of John Fowler, whose distinctive colour-palette became very evident in the house.

|

| Blithfield Hall: the 16th century first-floor Great Chamber, as redecorated by Lady Bagot with the advice of John Fowler. Nicholas Kingsley. Some rights reserved. |

In 1961, Nancy, Lady Bagot, bought the freehold of Blithfield Hall from the family will trust, thus ensuring that she could continue to cherish and restore the house after the death of the 6th Baron. In the 1980s she took the difficult decision to subdivide the house. A number of modest flats were created in the outbuildings, the south and west ranges were sold as separate houses, and the family retained the principal rooms in the north range. In 1999, the main part of Blithfield Hall was handed over to the great-nephew of the 6th Baron, Charles James Bagot Jewitt (b. 1965), who with his wife now occupies the main part of the house.

|

| Blithfield Hall: the south front in recent years. |

Bachymbyd, Llanynys, Denbighshire

|

| Bachymbyd: a drawing from a Graingerised copy of Thomas Pennant's Tour in Wales, 1781, perhaps by Moses Griffith. Image: National Library of Wales. |

Descent: John Salusbury (fl. c.1500); to son, Piers Salesbury; to son, Robert Salesbury (fl. 1546); to son, John Salesbury MP (d. 1580); to son, Sir Robert Salusbury (d. 1599); to son, John Salusbury (d. 1608); to uncle, John Salusbury (d. 1611); to brother, William Salusbury (d. 1660); to second son, Charles Salusbury (d. 1666), who built the house; to daughter, Jane Salusbury (d. 1695), wife of Sir Walter Bagot (1645-1705), 3rd bt.; to son, Sir Edward Bagot (1674-1712), 4th bt.; to son, Sir Walter Wagstaffe Bagot (1702-68), 5th bt.; to son, Sir William Bagot (1729-98), 6th bt., 1st Baron Bagot; to son, William Bagot (1773-1856), 2nd Baron Bagot; to son, William Bagot (1811-87), 3rd Baron Bagot; to son, William Bagot (1857-1932), 4th Baron Bagot, who sold as part of Pool Park estate in 1928... Mr. & Mrs G.H. Higham (fl. 1958)... A.R. Rowland (fl. 2010).

Pool Park, Efenechtyd, Ruthin, Denbighshire

The estate apparently originated as one of the five deer parks associated with Ruthin Castle, which was sold in the early 16th century to John Salesbury, who held it alongside Rhug and Bachymbyd. In the 17th century the estate was divided between the two sons of William Salusbury, with Bachymbyd and Pool Park passing to his younger but favoured son, Charles Salusbury. When Charles died without male heirs, it passed to his only surviving daughter Jane, who in 1670 married Sir Walter Bagot of Blithfield. Little seems to be known of the house that the Bagots acquired, although a view of the interior of the hall suggests that it had probably been rebuilt by the Salusburys in the Jacobean period.

|

| Pool Park, Ruthin: a view of the interior of the hall of the old house, which was replaced in the 1820s. Image: Thomas Lloyd. |

The grounds of Pool Park were apparently landscaped in the later 18th or early 19th century, either for the 1st Lord Bagot, or perhaps more plausibly, given the antiquarian references with which the grounds were decorated, by the 2nd Baron, who inherited in 1798.

|

| Pool Park: an old postcard showing the house in about 1910, with the applied half-timbering intact. |

The 2nd Baron was certainly responsible for rebuilding the house of the Salusbury family in 1826-29 to the designs of John Buckler, who is believed to have remodelled Blithfield a few years earlier. The local architect Benjamin Gummow was also involved, no doubt as clerk of works or site architect. The house is in the neo-Elizabethan style, with the main block and original service rooms all contained within a single symmetrical block with an E-plan front elevation and a symmetrical seven-bay side elevation. The centre of the entrance front is composed of three bays either side of a two-storey porch which is rather tightly squeezed into the composition, and which stands in front of a big central gable. At either end of the facade are boldly projecting wings, also crowned with tall gables. There are dormers in the roof, as well as tall chimneys rising at regular intervals along the ridge, and the windows are all mullioned and transomed - mostly of two lights but of three in the wings. Round the corner, the side elevation has a gabled central projection with an oriel window on the first floor, and to either side, further gablets also placed above oriel windows.

|

| Pool Park: the house in 1954. Image: Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Wales. Crown Copyright, reused under the Open Government Licence. |

The upper walls of the house were in the late 19th century decorated with small-scale applied half-timbering. The intensely Victorian effect of this makes it seem unlikely that it was part of the original design, but this does appear to be the case. When the semi-timbering was removed in the 1930s, leaving only the carved bargeboards on the gables, it was replaced by plain white stucco, and the ground-floor walls were painted white to match. This leaves the yellow sandstone porch sticking out like a sore thumb. Inside, little of the original interior decoration survives, but there is a striking Imperial staircase which seems to have been created in the early 20th century, perhaps by a tenant. It incorporates decorated vase-shaped 17th century balusters, figurative panels, and other reused woodwork which is said to have originally come from a house called Clocaenog. The house was never used as a principal residence by the Bagots, and was let to a series of tenants, including George Richards Elkington, the Birmingham electroplater, and Robert Blezard, a brewer from Liverpool.

|

| Pool Park: the staircase, soon after 1995. Some elements of the decoration have been removed from the site for safe-keeping. Image: Lack family |

Descent: Charles Salusbury (d. 1666); to daughter, Jane Salusbury (d. 1695), wife of Sir Walter Bagot (1645-1705), 3rd bt.; to son, Sir Edward Bagot (1674-1712), 4th bt.; to son, Sir Walter Wagstaffe Bagot (1702-68), 5th bt.; to son, Sir William Bagot (1729-98), 6th bt., 1st Baron Bagot; to son, William Bagot (1773-1856), 2nd Baron Bagot; to son, William Bagot (1811-87), 3rd Baron Bagot; to son, William Bagot (1857-1932), 4th Baron Bagot; to second cousin, Gerald William Bagot (1866-1946), 5th Baron Bagot; sold 1937 to North Wales Counties Mental Hospital; transferred 1948 to NHS; sold 1992.

Pype Hayes Hall, Erdington, Warwickshire

A much-altered timber-framed house, dating originally from the late 16th or early 17th century, when the estate belonged to the Arden family of Park Hall, Castle Bromwich. Externally, the main feature is a row of tiny wooden gables on the roof-line, and there are the usual wings projecting on either side of the hall range. When Robert Arden died in 1643 the estate passsed to his sister Dorothy, who had married Hervey Bagot of Blithfield, and it then became a secondary seat of the Bagot family.

|

| Pype Hayes Hall: entrance front. The original 17th century house is well concealed by 18th and 19th century alterations. |

The house was remodelled in the mid 18th century, when the whole house was rendered, the present staircase was built and the pedimented porch with Tuscan columns added. A new stable block was built in 1762, which may date these changes, and the landscaping of the park, with its lake may also have been carried out at the same time. In the mid 19th century, the house was doubled in depth and a new neo-Jacobean garden front was created.

|

| Pype Hayes Hall: the neo-Jacobean rear elevation added in the mid 19th century. |

Descent: Robert Arden (d. 1643); to sister, Dorothy, wife of Col. Hervey Bagot (1617-74); to son, Arden Bagot (1647-96); to son, Thomas Arden Bagot (1687-1729); to son, Egerton Bagot (1713-75); to kinsman, Rev. Walter Bagot (1731-1806); to son, Rev. Egerton Arden Bagot (1777-1861); to nephew, William Walter Bagot (1847-93); to widow, Lucy Matilda Bagot (1847-96); to daughter, Frances Anna Mary (1869-1915), wife of Harry Richard Reginald Bagot (1860-1908) and later of Henry Bennett Ewins-Burrell-Ewins, who leased the estate to J. Rollason and then sold the freehold to him in 1906; sold 1919 to Birmingham City Council; sold 2015.

Ashtead Park, Surrey

The first manor house of which anything is known was a one- and two-storey semi-timbered building of the late 15th or early 16th century, which stood immediately next to St Giles' church. The estate was bought by Sir Robert Howard from the Dukes of Norfolk in about 1680, with the intention of making it his principal seat, and he lost no time in building a new house on a new site in the grounds, though the old building was converted for use as a dairy and apparently not pulled down until the late 18th century.

|

| Ashtead Park: this sketch of c.1689 shows the square house built by Sir Robert Howard and described by John Evelyn and Celia Fiennes. |

‘a Square building, the yards and offices very Convenient about it, and severall Gardens walled in. All the windows are sashes and Large squares of glass; I observ'd they are double sashes to make ye house the warmer, for it Stands pretty bleake. Its a brick building. You Enter a hall which opens to the Garden, thence to two parlours, drawing-roomes and good staires, there are abundance of Pictures, above is a Dineing roome and drawing roome with very good tapistry-hangings of Long standing... There are good pictures of the family, Sr Robert's Son and Lady, which was a Daughter of the Newport house, with her Children in a very Large Picture. There is fine adorrlements of Glass on the Chimney and fine marble Chimney pieces, some Closets with Inlaid floores, its all very neate and fine with the several Courts at the Entrance".

|

| Ashtead Park: drawing by John Hassall, n.d. [c.1800]. Image reproduced by permission of Surrey History Centre (ref. 4348/2/87/3). |

The late 17th century house was rebuilt in 1790 as a seven-by-three-bay block, two-and-a-half storeys high, which was designed by Joseph Bonomi (1739-1808) for Richard Bagot Howard, but executed by Samuel Wyatt (1737-1807), who was something of a protégé of the Bagots. A plain, rather Soanian, stable block to the west to the west was built at the same time. The original appearance of the house is recorded in a watercolour by Hassall, which shows that it was considerable altered in the 1820s or 1830s, when much grander centrepieces were created on both the main fronts. Some components of the original interior decoration survive, including a fine Adam-style staircase with a pretty balustrade; the Old Library, with original bookcases and simple neo-classical plasterwork; and best of all, the circular Saloon, which has alternate niches and pairs of scagliola Doric columns around the room, and further pairs of columns framing the doorcases.

After Pantia Ralli bought the estate in 1889, it was again altered, with low wings being added to the east and west, and a new neo-Jacobean entrance hall and library being created. He was also responsible for the semicircular formal garden on the north front and the removal of the east garden. On his death in 1924 the estate was put up for sale in fifty-one lots. The main house and surrounding parkland to the south of the site was purchased by the Corporation of London for use as a boarding school, in which use it continues. The northern part of the park remains as open space owned by Mole Valley District Council.

|

| Ashtead Park: the house as altered c.1890, from an old postcard. |

Descent: Sir Robert Howard (1626-98), kt.; to son, Thomas Howard (d. 1701); to widow, Lady Diana Howard (d. 1733), later the wife of the Hon. William Fielding (d. 1723); to Henry Bowes Howard (d. 1757), 4th Earl of Berkshire and, from 1745, 11th Earl of Suffolk; to younger son, Hon. Thomas Howard (d. 1783); to niece, Frances Howard (1746-1818), wife of Richard Bagot (later Howard) (1733-1819); to daughter, Mary (1785-1877), wife of the Hon. Fulke Greville Upton (later Howard) (d. 1846); to cousin, Lt-Col. Ponsonby Bagot (1845-1921); who sold 1880 to Sir Thomas Lucas, 1st bt.; sold 1889 to Pantia Ralli (d. 1924); sold to City of London as a new home for the City of London Freemen's School.

Continue to part 2 of the post

Continue to part 2 of the post

Sources

Burke's Peerage & Baronetage, 2003, pp. 215-19; Burke's Landed Gentry, 1850, i, p. 43; Lord Bagot, Memorials of the Bagot family, 1824; F.A. Crisp, Visitation of England & Wales, vol. 10, 1913, pp. 138-53; vol. 13, 1905, pp. 1-8; Sir N. Pevsner, The buildings of England: Staffordshire, 1974, pp. 72-74; A. Bayliss, The life and works of James Trubshaw, 1978, pp. 13-14; J.M. Robinson, The Wyatts, 1979, pp. 11, 23, 256; E. Hubbard, The buildings of Wales: Clwyd, 1986, pp. 263-64; J. Ingamells, A dictionary of British and Irish travellers in Italy, 1701-1800, 1997, pp. 39-40; M. Wood, John Fowler: prince of decorators, 2007, pp. 135-39; Sir H.M. Colvin, A biographical dictionary of British Architects, 4th edn., 2008, pp. 180, 194, 1002, 1059, 1194; M. Tree & M. Baker, Forgotten Welsh houses, 2008, pp. 142-43; T. Mowl & D. Barre, The historic gardens of England: Staffordshire, 2009, pp. 89-93, 166, 219; pl. 28; N. Bagot, Blithfield Hall: a country house saved, 2011; J.M. Robinson, James Wyatt: architect to George III, 2012, pp. 2-3; http://yba.llgc.org.uk/en/s-SALU-RUG-1525.html.

Revision and acknowledgements

This post was first published 8 December 2017 and updated 4 October 2020. I am grateful to Brian Bouchards for tracking down the 17th century sketch of Ashtead Park.

Bagot goats and the Abbot's Bromley horn dance are both part of the story of the Bagot family:

ReplyDeletehttps://bagotgoats.co.uk/about-bagot-goats/

http://baggetthistory.com/bromley.html

John Bagot (Baggett) is my 9th Great Grandfather, son of Sir Hervey Bagot. The spelling of the last name changed once they migrated to America. Thanks for putting together this article and for the research that you did.

ReplyDeletePerhaps the label "Ancient families" should be added to the Bagot posts?

ReplyDeleteThanks for pointing out this oversight!

DeleteHi Nick, thank you for this very interesting post about the Bagots and Blithfield. I'm descended from Walter Bagot (1557-1623), his daughter Frances is my 11 x great-grandmother. I'm thoroughly enjoying your blog. Regards, Rachel

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete