The Beauclerk family descends from the elder illegitimate son of King Charles II (1630-85) and his most famous mistress, Nell Gwyn (1650-87). Nell's background is obscure, but her illiteracy and ready Cockney wit suggest she was brought up in London's poorest districts. As a teenager she became an orange-seller and then an actress in the London theatres. The casting of women in female roles on the stage was a novelty in Restoration London, and the (usually good-looking) young women who took up this new career were widely suspected of immorality. Coupled with her personal background, this helps to explain why she achieved less ready acceptance at Court than the king's other mistresses, who were ladies, even if they were ladies of negotiable virtue.  |

| Nell Gwyn, by Simon Verelst |

The king never felt able to give Nell a peerage, as his did with his other two leading mistresses, Barbara Villiers (Duchess of Cleveland) and Louise de Kerouaille (Duchess of Portsmouth). Nell seems not to have particularly cared about that, but did want titles for the two sons she bore the king: Charles (1670-1726) and James (1671-81), who died while at school in Paris. The two boys had neither surnames nor titles until 1676, when Nell is said to have made a scene about the matter: the king responded by calling them Beauclerk (pronounced 'Boh-clare') and making the elder boy Earl of Burford and Baron Heddington, while James was given the rank of an Earl's younger son and the courtesy title Lord Beauclerk. Charles was further promoted to the Dukedom of St. Albans at the beginning of 1684, just eight days after the death without heirs of Charles' old friend, Henry Jermyn, Earl of St. Albans, had made the title available.

In the 1670s and 1680s Nell Gwyn secured for herself and her son both pensions and property. In London, she was given a lease (and in 1676 the freehold) of 79 Pall Mall, a house which was convenient for the king's court and which had (perhaps coincidentally) previously been occupied by the Earl of St. Albans. At Windsor, a new house (Burford House) was built for her to the south of the castle, which was a substantial residence although it did not have an attached estate. In 1681 the king granted her the 3,723 acre Bestwood Park estate in Nottinghamshire, a hunting preserve in Sherwood Forest, where there was a medieval semi-timbered hunting lodge with 38 rooms. This estate, which remained in the family until 1940, was never, however, regarded as a place of residence until 1860s, when the 10th Duke built a large new house there. These properties descended, on Nell's death in 1687, to the young Duke of St. Albans, but they did not generate much income, and even with the Duke's pensions and official positions his income is thought to have peaked at around £10,000 a year in the early years of Queen Anne's reign, which was hardly sufficient to sustain ducal splendour. Charles II's other illegitimate sons married great heiresses, but the Duke of St. Albans married Diana de Vere, daughter of the 20th and last Earl of Oxford, who was regarded as a great beauty and who had a pedigree stretching back to the Norman Conquest, but whose material expectations as heiress to her father were very limited. The marriage produced twelve children, including nine sons, eight of whom survived to adulthood, although all three of the daughters seem to have died young. Descendants of the three eldest sons have all inherited the Dukedom in turn and their careers are described in the genealogy in part 2 of this post, while two of the younger sons founded cadet branches of the family which will be the subject of future posts.

The 1st Duke was in a position of some political delicacy at the time of the Glorious Revolution in 1689, since he was a Stuart by blood even if he was illegitimate. However, his uncle James II seems to have managed him badly, urging him to convert to Roman Catholicism and planning to send the young man to Hungary with a Catholic tutor in the face of his disinclination. He was given command of a regiment in 1687 (aged 17!) and although the Duke seems to have been in Europe at the time of William III's invasion, his regiment was one of the first to join King William's cause. During the 1690s, the Duke became a close associate of William III. He was a Whig in politics, and thus eclipsed during the latter part of Queen Anne's reign, but he maintained his principles, supported the Hanoverian Succession and was close to George I. Although there was a rift between George I and his son in which the Duke and his wife became involved, the 2nd Duke was even closer to George II and Queen Caroline than their fathers had been. Up until the time of the 2nd Duke's death in 1751, therefore, royal goodwill, offices and pensions combined to keep the Dukes of St. Albans in the style expected of their rank, but that was to change radically in the next generation.

Over more than two centuries, the Dukes of St. Albans often married well, to heiresses whose wealth or property could have put the family on a sound financial footing, but through misfortune in the matter of heirs, or through habits of indolence or dissipation, these inheritances have slipped through their fingers. The 3rd Duke is the earliest instance of this. His father and his uncle, Lord William Beauclerk, had married the two daughters and co-heiresses of Sir John Werden, 2nd bt., who owned estates in Lancashire, Cheshire and Berkshire. Sir John's second wife died at much the same time as the 1st Duke, in 1726, and his sons-in-law at once became apprehensive that he would marry again and produce a son who would inherit the Werden estates to the destruction of their own expectations. Sir John did marry again - twice - but his third wife had no children and left him £30,000, while his fourth wife produced only a daughter, who seems to incurred her father's displeasure and was cut out of his will. Sir John survived both his Beauclerk sons-in-law, living until 1758, by which time the bulk of his property had already been made over to his daughter Charlotte, widow of Lord William Beauclerk, and her son Charles Beauclerk (c.1728-75), whose son George (1758-87), succeeded briefly as 4th Duke of St. Albans in 1786. The 3rd Duke was not totally cut out of Sir John's will, but he was only a minor beneficiary, receiving a life interest in the site of Durham House in London and an annuity. He had already given signs of dissolution and excess by siring an illegitimate child while still a schoolboy at Eton and by the failure of his marriage after less than three years, and Sir John was perhaps disinclined to reward such conduct.

The 3rd Duke was married in 1752 to Jane Roberts, heiress of Sir Walter Roberts, 6th bt., of Glassenbury Park (Kent), whose father was already dead, and who brought him estates in Kent (Cranbrook, Goudhurst, Hunton and Brenchley), Surrey (Streatham and Peckham) and Leicestershire (Wigston Magna, Frisby and Galby), with the latter passing to him outright on his marriage. But within two and a half years their marriage had foundered on the grounds of his cruelty and unfeeling treatment of his wife, leaving him with no legitimate issue. Jane received an income of £2,000 a year and the use of the secondary house on the Kent estate (Gennings at Hunton), while the 3rd Duke retained a life interest in the Kent and Surrey property, which provided a useful addition to his income in view of the failure of his expectations from his grandfather. Once separated from his wife, the 3rd Duke embarked on a 'glittering crescendo of feats of incompetence quite unparalleled in the lives of any other dukes in the eighteenth century, and involving mistresses, elopements, debts, bankruptcy, fleeing from creditors, self-imposed exile, imprisonment', and a further five illegitimate children. By the time the 3rd Duke died he was pressed on all sides by creditors, and had sold almost all his freehold property. Only Bestwood, which was entailed, survived to be passed on to his first cousin once removed, George Beauclerk (1758-87), 4th Duke of St. Albans. As we have seen, the 4th Duke was the ultimate principal beneficiary of the Werden family estates, but he died young and without issue. The heir to the Dukedom and to Bestwood was his father's first cousin, the 2nd Baron Vere of Hanworth, who was not descended from the Werdens, so the 4th Duke bequeathed his share of the Werden estates to his father's elder sister, Charlotte Drummond. She was the widow of the immensely rich banker, John Drummond, so this was a quixotic and sentimental gesture which the 5th Duke can hardly have appreciated.

Aubrey Beauclerk (1740-1802), 2nd Baron Vere of Hanworth, who became 5th Duke of St. Albans in 1787, was the son of Lord Vere Beauclerk (1699-1781), the third son of the 1st Duke, who had made a career in the Navy and been created a peer in his own right in 1750 as Baron Vere of Hanworth. Lord Vere was another member of the Beauclerk family who made an advantageous marriage, for Hanworth Park in Middlesex was an estate which he and his wife, Mary Chambers, inherited from her father in 1736. They were also among the heirs of Mary's aunt, Lady Betty Germaine (1680-1769), who had already settled £10,000 on Mary at the time of her marriage, and although they did not, as they hoped, inherit the Drayton House estate in Northamptonshire from her, she left each of them £30,000 in Government stocks and her niece a £20,000 cash legacy as well. When their son Aubrey came into the Dukedom and the Bestwood estate in 1787, it must have seemed that the Dukedom was at last allied to the resources required to support the dignity. Unfortunately, the conjunction was short-lived. His wife died in 1789 and from 1793 Hanworth Castle was leased out. In 1797 it burned down, and in order to rebuild it, the 5th Duke sold a significant collection of art which he had acquired in Italy. The new house was much smaller than its predecessor, but was almost finished by the time of the 5th Duke's death in 1802. His eldest son, Aubrey Beauclerk (1765-1815), 6th Duke of St. Albans, inherited, but in 1811 sold much of the estate (not including the new house). He died in 1815, leaving a widow and an infant son, the 7th Duke. While the title and entailed estate passed to his son, his unentailed property and personal estate, including the house at Hanworth, was effectively left to his widow absolutely. Had the infant 7th Duke survived to adulthood, his mother would no doubt have left him the bulk of her estate, but he did not: they both died of a fever on 19 February 1816. To make matters worse, the 6th Duke's two younger brothers had been stirring up trouble over his will and his widow's conduct. They accused her of having an affair and suggested that the 7th Duke might be her lover's son and not her husband's. Whatever the truth of this (and it seems quite plausible and circumstantial), the Duchess not unnaturally resented the accusations, and made a will leaving all her property to her sister, Mrs. Laura Dalrymple, rather than passing it back to the Beauclerks. Once again, the Beauclerks had contrived to lose control of an inheritance gained through marriage.

With the death of the infant 7th Duke the title and entailed estate passed to his uncle, Lord William Beauclerk (1766-1825), the second son of the 5th Duke, who became the 8th Duke of St. Albans. He had pursued a naval career, retiring as a Commander, and lived from 1816 in a rented house in Surrey called Upper Gatton. He married twice, on both occasions to heiresses. His first wife, Charlotte Carter-Thelwall (d. 1797), brought him the Redbourne Hall estate in Lincolnshire, together with lands at Pickworth (Lincs) and elsewhere, but their only child died in infancy. His second wife, Maria Jenetta Nelthorpe (d. 1822), brought him Little Grimsby Hall (Lincs) and also a further fourteen children, twelve of whom survived to maturity. It is in this generation of the family that there first becomes apparent a certain mental instability which became more marked later: two of the 8th Duke's children died in a mental hospital at Ticehurst (Sussex). To accommodate his large family, he built a new wing at Redbourne Hall, which became the principal seat of the family for the next half-century. Little Grimsby Hall was bequeathed to his second surviving son, Lord Frederick Charles Peter Beauclerk (1808-65), whose descendants owned it until 1943 and will be subject of a future post.

When the 8th Duke died in 1825, his title and estates at Bestwood, Redbourne and Pickworth descended to his eldest son, William Aubrey de Vere Beauclerk (1801-49), 9th Duke of St. Albans. Although William was regarded at the time as both unintelligent and ill-informed, it was hoped that he would marry Fanny Gascoyne, a great friend of his sister Charlotte, who would have brought him £10,000 a year, though in the end she chose Lord Cranborne, heir to the Marquess of Salisbury. In 1824 the 8th Duke took his son to a party at Holly Lodge in Highgate (Middx), which was the seat of Harriot Coutts, the exceedingly rich widow of the banker Thomas Coutts, in the hope that he might meet an eligible young woman there. The 8th Duke, himself a widower for a second time, may also have nursed hopes of securing Mrs Coutts as his third duchess, but unexpectedly the relationship that flowered was between Mrs Coutts, and his son, who was half the lady's age. .jpg) |

| Harriot Coutts (d. 1837), later Duchess of St. Albans |

Like Nell Gwyn, Harriot had begun life as an actress, but her beauty and intelligence captivated Thomas Coutts, who admired and supported her for years before his first wife died and he was free to marry her in 1815. When he died in 1822 she was his principal legatee, inheriting at least half a million pounds and possibly more, and becoming the senior partner in Coutts Bank. Money opens many doors, but in Regency England it did not open them all, and there were plenty of ladies in high society who would not receive her because of her low birth. It is said to have been a mutual interest in Shakespeare which first kindled her friendship with the 9th Duke, and although for a long time she did not encourage him, they were married in 1827. It must, at some level, have been a marriage of convenience, for Harriot gained the title of Duchess which made her harder to ignore socially, and the Duke benefited from her almost limitless wealth: as a wedding present she gave him a cheque for £30,000 and the manor of Woodham Walter (Essex), valued at £26,000. Harriot died in 1837 and left her husband £10,000 a year, Holly Lodge and her town house at 80 Piccadilly, all for life, but the bulk of her estate passed to Thomas Coutts' granddaughter, Angela Burdett (1814-1906), who took the additional name Coutts and became one of the greatest 19th century philanthropists.

The 9th Duke married again in 1839, this time to a younger woman who could provide him with a family: a son and heir was born in 1840 and a daughter in the following year. In the late 1840s the Duke, who had deteriorating eyesight, had a hunting accident and suffered a blow on the head which left him subject to epileptic fits, and he died in 1849, when his son was just nine years old. It may not have been an auspicious beginning, but William Amelius Aubrey de Vere Beauclerk (1840-98), 10th Duke of St. Albans, was to become the most energetic and admirable of his family, active in politics, locally and nationally, estate management, and sporting and literary pursuits. He inherited the family estates at Bestwood, Redbourne, Pickworth and Woodham Walter, but sold the latter two properties to fund the building of the first really grand country house the family had ever owned at Bestwood Lodge, choosing as his architect the inventive Samuel Sanders Teulon, who delivered a characteristically unconventional building. He also invested in developing Bestwood Colliery, exploiting the rich seam of coal which lay under the Bestwood estate, and creating an important new source of revenue for the family. He married twice and had children by both marriages, but he was singularly unfortunate in his sons, in whom the mental instability referred to earlier returned with a vengeance. His eldest son, Charles Victor Albert Aubrey de Vere Beauclerk (1870-1934), 11th Duke of St. Albans, suffered from severe depression and paranoid delusions, and was confined from 1899 in the same mental hospital at Ticehurst where his great-aunt and great-uncle had been treated. The 10th Duke's youngest son, Lord William Huddleston de Vere Beauclerk (1883-1954) was sent to Eton, but set fire to a building there, and spent his life confined in mental institutions. Only the middle son, Osborne de Vere Beauclerk (1874-1964), who succeeded his elder brother in 1934 as 12th Duke of St. Albans, was comparatively normal, and even he recognised in himself a susceptibility to mental illness, which he sought to control throughout his long life. Perhaps as a result, he exhibited an inconsistency of manner which meant he had few friends, and he became increasingly eccentric as he got older. He married, but he and his wife lived increasingly separate lives and had no children, so that when the 12th died, the title passed to a second cousin, descended from a younger son of the 8th Duke.

The 10th Duke's second wife came from an Irish family, and in 1880 she inherited Newtown Anner (Co. Tipperary) from her mother. With the 11th Duke in an institution and his affairs in the hands of trustees, Bestwood Lodge was leased out from 1915 (and sold in c.1943) and Redbourne Hall was sold in 1917. Newtown Anner therefore became the country seat of the 12th Duke by default. After he and his wife separated, it was the Duchess who was usually resident at Newtown Anner, while the Duke lived chiefly in London. The Duchess died in 1953 and for a time the Duke took more interest in the place, but in 1958 he made the estate over to Col. John Silcock (1913-2005), his wife's daughter-in-law's second husband, and he ended his days at Holker Hall in Lancashire, the seat of his nephew.

Burford House, Windsor, Berkshire

The house later called Burford House seems to have been built or remodelled in the 1670s by King Charles II for his mistress, Nell Gwyn, on a site to the south of Windsor Castle which had formerly been part of the castle gardens or vineyard. It is less a country house than a satellite of the castle, but it was the main residence of the first two Dukes. The architect is unknown, but the Office of Works team was not, apparently, involved in its construction, as there are no payments relating to the project in the Works accounts until 1678, the year when Nell Gwyn actually moved in, when one John Bodevin was paid £100 for unspecified repairs and Antonio Verrio was paid for decorating the staircase with scenes from Ovid. In 1680, the freehold was granted to trustees for Nell Gwyn, with remainder to her son by the king, then known as the Earl of Burford, hence the name of the house. The building is shown in a number of views of Windsor and the castle in the 17th and 18th centuries.

|

| Burford Lodge, Windsor: detail of the Kip engraving showing the house in the foreground, c.1708 |

Johannes Kip made an engraving after a painting by Leonard Knyff in about 1708, which depicts the house, with the castle in the background. This view, and a painting of c.1745 in the Royal Collection which shows the view down the Long Walk from the castle, give a fairly clear idea of what the house was like. It was a fairly plain rectangular two-storey red brick house, rather typical of its date, with a double pile plan and an eleven bay elevations to the east and probably to the west as well. The two bays at either end of the elevations were brought slightly forward, and a wooden cornice supported a hipped roof with dormers. The house was approached from the road to the west through a forecourt with a pair of porter's lodges either side of the entrance. On the east side was an extensive garden with a plain fifteen-bay brick greenhouse set at right-angles to the house, which would seem to have been demolished by the time of the view of c.1745.

|

| Burford Lodge: the house as remodelled c.1779-82, can be seen in the background of this view of Queen's Lodge by James Fittler, 1783. |

In 1749, the house was described as "a stately and handsome seat with beautiful gardens that extend to the park wall…..[the 2nd Duke] is at present making farther improvements by opening a view into the High Street of the town". The 3rd Duke, who was a great spendthrift, sold Burford House to King George III in 1779 for £4,000, and it became an annexe to the Queen's Lodge that the king constructed just to the north, and was renamed Lower Lodge. The two houses became the royal family's residence at Windsor (the castle then being old-fashioned and in poor repair), and the younger princesses lived in the Lower Lodge. By 1782 the house had been remodelled, with the conversion of the dormered attics into a third full storey, and the addition of a castellated parapet and a coat of stucco. The works were supervised by Sir William Chambers as Comptroller of the Royal Works, and the detailed plans were drawn up in his office, but it is believed that the design originated with the King himself, who had a considerable reputation as an amateur architect: a reputation not obviously justified by the barrack-like quality of the Queen's Lodge and Lower Lodge!

|

| Burford House: the buildings as remodelled by Edward Blore c.1842. |

After Queen Charlotte’s death in 1818, the Lower Lodge became the property of Princess Sophia, who gave it up to her brother, the Prince Regent. During his extensive transformation of the castle and park at Windsor, he demolished the Queen’s Lodge in order to improve the view of the Long Walk, and it was intended that Burford House would also be pulled down. This never happened, however, and it was further altered by Edward Blore in c.1842, who gave it a more substantial Gothic refronting and made some additions. It reverted to the name Burford House, and became the married quarters for workers in the Royal Mews. In the 1940s there was yet another remodelling, when it was adapted to form eleven separate flats, and very few if any features now remain to remind the visitor of its 17th century origins.

Descent: granted 1680 to Nell Gwyn (1650-87); to son, Charles Beauclerk (1670-1726), 1st Duke of St Albans; to son, Charles Beauclerk (1696-1751), 2nd Duke of St. Albans; to son, George Beauclerk (1730-86), 3rd Duke of St. Albans; sold 1779 to King George III and given to Queen Caroline (d. 1818); to daughter, HRH Princess Sophia (1777-1848); given to King George IV (1762-1830) and descended with the Crown as part of the Windsor Castle estate.

Bestwood Lodge, Nottinghamshire

A royal hunting lodge in Sherwood Forest was built in 1284 close to the site of the present house, and a park was enclosed around it in 1349 which is marked on the remarkable medieval map of Sherwood now at Belvoir Castle. The lodge was built of timber and lath and plaster and had a slate roof, and in 1573 and again in 1593 the keeper of the park, Thomas Markham (d. 1606) made repairs to the lodge. Further work was done in 1627, and by 1650 the lodge contained 38 rooms but was in disrepair again. It was estimated that if it was pulled down the value of the materials would be only about £100 more than the cost of demolition. By 1681, King Charles II had granted a lease of the park to his mistress, Nell Gwyn, and before her death in 1687 she had acquired the freehold. The property passed to her son, the Duke of St. Albans, and it descended in his family, but since successive dukes lived elsewhere and were usually short of funds, the timber-framed Bestwood Lodge survived until the mid 19th century, no doubt with some alterations and further repairs. In the late 18th century, Lord Amelius Beauclerk had built what sounds like a habitable folly near the old house: a 'strange architectural toy' in the form of a 'naval castle' which 'closely resembled a warship' and was the exact length of a naval quarterdeck, with rooms inside modelled on ship's cabins. Both houses were pulled down in 1860 by the 10th Duke, who came of age in 1861. The first wife of the 9th Duke had been the widow and principal heiress of the millionaire banker, Thomas Coutts, and although she left the bulk of her fortune to Coutts relatives, the annuity she left to her husband meant that the 10th Duke was in a better position to build extravagantly than any of his predecessors.

The new Bestwood Lodge was designed on a slightly higher site than its predecessors, which commanded a view over the city of Nottingham. The architect was the vigorous and crazily inventive Samuel Sanders Teulon (1812-73), and Bestwood is one of his five largest houses. It was constructed in red brick with generous stone dressings, and is essentially in an early Gothic style, with an exceptionally spiky skyline. Photographs of the house when it was first built show that it had then a visual coherence and a picturesque composition, especially as seen from the west, which is not apparent now, when injudicious later alterations have obscured much of Teulon's original scheme.

|

| Bestwood Lodge: the house as first built, c.1865. |

|

| Bestwood Lodge: the entrance front after the construction of the conservatory block c.1870. |

The house occupies a platform from which the land falls steeply away to the north-east and south-east, and it is therefore approached from the west. The drive leads into a forecourt with the main block of the house to the east and an enclosing service wing to the north, which terminates in a building with a crowstepped gable-end and a bellcote, suggestive of a chapel but in fact housing the servants hall (a frivolity of which The Ecclesiologist disapproved). The forecourt is now also enclosed on the south by a second wing which was first built about five years after the house was finished as a conservatory range, but which was radically remodelled as a drill hall after 1896, with very little sensitivity, in the most lumpen timber-framed manner. A rough brick octagonal tower with a tall roof was added at the junction with the main house at the same time.

|

| Bestwood Lodge: detail of the porch when the house was first built, c.1865. |

Fortunately, the approaching visitor does not notice the wing particularly, for the eye is caught and held by the extraordinary porch on the main block, which scampers up the house with great agility in a tour-de-force of what Mark Girouard termed 'acrobatic Gothic'. Flying buttresses clasp the porch and a canted oriel window above it, and the line of the porch is further carried up by a second canted bay at attic level and then by a slender tower with a pyramidal roof embellished with lucarnes and a tall weathervane. The archway of the porch itself is decorated with carved heads of Robin Hood and his Merrie Men carved by Thomas Earp, who also executed panels of scenes from local history elsewhere in the building.

|

| Bestwood Lodge: the south front in the late 19th century. |

|

| Bestwood Lodge: the south and east fronts as first built, c.1865. |

The other principal facades of the building are those to the south and east. The south side is less playful than the entrance front, but hardly more restful. It is composed of six irregular bays, and has two storeys with gabled attics. Every bay stands in a different plane to its neighbours and is topped by a gable, tower or dormer of different form. The windows are mostly of plate tracery, but some are two lights and others three, while those on the end bay are wrapped around a canted two storey bow. The staircase windows on the first floor of the second bay project down into the ground floor and have stepped bases, while a slim turret with a conical cap projects towards the right hand end. Despite all this irregularity there was originally a detectable balance, well short of symmetry, between the left and right hand halves of the facade, which was spoilt by the addition of the drill hall wing, that stands forward of the rest of the elevation.

|

| Bestwood Lodge: the east front after the addition of the staircase tower. |

The east side of the house has a recessed centre between two projecting wings, but is designed to express clearly that the left-hand part, mostly of three storeys, with large plate tracery windows and elaborate gables and dormers, belongs to the polite part of the house, whereas the right-hand section, mostly of two storeys, with much smaller and rather ugly square windows and tiny wooden dormers, belongs to the service wing. An exceptionally muscular tower, with two rows of lancet windows following the rise of the staircase inside, was added to the polite end of the elevation, probably in the 1870s, and further unbalances the composition.

|

| Bestwood Lodge: ground floor plan (omitting the conservatory/drill hall wing) (after Jill Franklin). |

Although Bestwood Lodge could not be called a small house, its plan suggests that it was perhaps conceived of more as a hunting lodge than as a full-blown country house. A considerable part of the footprint is taken up by a large central courtyard between the main rooms and the service wing, and the former comprise only a hall, drawing room, dining room, billiard room and study. The original interiors were badly damaged by a fire in 1885, and the best preserved room is now the two-storey, top-lit inner hall, which has a really chunky fireplace and a two-storey screen across one end.

|

| Bestwood Lodge: inner hall. Image: Best Western Hotels Ltd. |

The gardens were landscaped by Teulon and a 'Mr. Thomas' - perhaps the estate gardener - with terraces and lawns amid woodland, but were altered in the early 20th century and later. The Alexandra Lodge, NW of the house, is attributed to Teulon, but may not have been built until after his death, as it carries dates of 1877 and 1878. It is of brick and takes the form of a pair of lodge houses either side of an archway with a timber-framed room over the archway under a tall roof.

The house was generally let in the early 20th century, and was put on the market to pay the death duties arising from the death of the 11th Duke in 1934. Efforts to sell it in 1940 and 1943 were unavailing, but it was eventually sold to the Government, which had already requisitioned it for use as the headquarters of Northern Command. It remained in military use until the early 1970s, when the county and district councils combined to purchase the wooded parkland to the north-west, which became Bestwood Country Park in 1973. The house itself was converted into a hotel, now part of the Best Western Group. In a slightly ironic twist, the servants' hall, whose chapel-like appearance so distressed The Ecclesiologist, is now used as a wedding venue.

Descent: Crown granted 1681 to Nell Gwyn (1650-87); to son, Charles Beauclerk (1670-1726), 1st Duke of St Albans; to son, Charles Beauclerk (1696-1751), 2nd Duke of St. Albans; to son, George Beauclerk (1730-86), 3rd Duke of St. Albans; to first cousin once removed, George Beauclerk (1758-87), 4th Duke of St. Albans; to first cousin once removed, Aubrey Beauclerk (1740-1802), 2nd Baron Vere of Hanworth and 5th Duke of St Albans; to son, Aubrey Beauclerk (1765-1815), 6th Duke of St. Albans; to son, Aubrey Beauclerk (1815-16), 7th Duke of St. Albans; to uncle, William Beauclerk (1766-1825), 8th Duke of St. Albans; to son, William Aubrey de Vere Beauclerk (1801-49), 9th Duke of St. Albans; to son, Rt. Hon. William Amelius Aubrey de Vere Beauclerk (1840-98), 10th Duke of St. Albans; to son, Charles Victor Albert Aubrey de Vere Beauclerk (1870-1934), 11th Duke of St. Albans; to half-brother, Osborne de Vere Beauclerk (1874-1964), 12th Duke of St. Albans, who sold c.1943 to HM Government.

Hanworth Palace and Hanworth Park House, Middlesex

Immediately south of the medieval church of Hanworth was a moated hunting lodge acquired by Henry VII in about 1507, which according to Camden was Henry VIII's 'chief place of pleasure', and was referred to as Hanworth Palace. The Office of Works accounts indicate extensive works took place on the house, gardens and park in 1507-09. In 1532 the king gave the house and park to Anne Boleyn, and workmen at Hampton Court were diverted to fitting up new interiors and other works. Some of the exterior walls and chimneys were embellished by a painter with 'antike work', and Antony Toto and John de la Mayn set up and repainted 'certen antique heds brought from Grenewiche to Hanworthe at the kyng's comandment'. The site still has the remains of large Tudor walls and fireplaces, interpreted as being remains of the royal kitchens, but much of the site was built over in the 20th century to create a cul-de-sac called Seymour Gardens. Two later garden buildings in the entrance court at Hanworth have terracotta roundels with classical busts similar to those set into the walls of Hampton Court, and these could be the panels brought from Greenwich in 1532, but they are said to have been acquired in 1759 by Lord Aubrey Beauclerk and to have come from the Holbein Gate in Whitehall.

|

| Hanworth Palace: the house in the late 17th century. Image: London Metropolitan Archives |

The house was evidently remodelled in the 17th century by Sir Francis Cottington (c.1579-1652), 1st bt. and 1st Baron Cottington, who described his improvements to a friend:"There is a certain large room under the new building, with a fountain in it, and other rare devices, and the open gallery is painted by the hand of a second Titian. Dainty walks are made abroad, in so much that the old porter with the long beard is like to have a good revenue by admitting strangers".

The only illustration of the house at this time is a little hard to interpret, but seems to show a timber-framed house twelve bays square. This house was rebuilt or remodelled by the Chambers family, who had a ceiling painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723), more usually known as a portraitist. By 1738, it was a three-storey block of eight (7+1) bays, with a full-height canted bay in the centre. To one side was a lower and evidently older range, of two storeys with gabled dormers, but with the windows remodelled to match those of the main block. Above the centre of the main block was a tall cupola. This house burned down in 1797, and was almost totally destroyed apart from the stable block, which survived and was converted into flats, now called Tudor Court, c.1924.

|

| Hanworth Palace and church in 1738, from an estate map. Image: London Metropolitan Archives ACC/1023/379. |

The stable block was either rebuilt or remodelled for the 1st Lord Vere of Hanworth to the designs of Sanderson Miller (who never visited the site but supplied a design at the request of a mutual friend in 1750), and consists of a two-storey L-shaped brick block of symmetrical design, with battlemented corner towers. The present Gothic windows are a later alteration, since they are not shown on the drawing of the park below.

|

Hanworth Palace: a drawing of c.1801 showing the new house and the stable block as originally designed by Sanderson Miller in 1750.

Image: Yale Center for British Art. |

|

| Hanworth Park: the stable block in the mid 20th century, after conversion to flats. |

A new house was built between 1798 and 1802 on the original site to the designs of an unknown architect; this was a much smaller five bay, three-storey block recorded in an early 19th century drawing. This in turn was replaced by a larger new house on a site about half a mile to the north in 1828 for Henry Perkins, the London brewer (a partner in Barclay & Perkins), who was the tenant of the estate and later bought the freehold. This house just about survives today, and has a long frontage of eleven bays in London stock brick, grouped 2-2-3-2-2, of two storeys above a high basement. In the centre is a portico with four Greek Doric columns approached up a grand flight of steps. All along the front, and above the portico, is a two-storey cast-iron veranda. The end pavilions have hipped roofs, and in the centre is a low pediment with incongruous and presumably later decorative bargeboards. To the rear of this block are two long wings. That on the east is perhaps a contemporary service wing, but that on the west was rebuilt in a loosely Italianate style by the Perkins family c.1860. It has groups of narrow arched windows, and terminates in a stumpy campanile. Inside, there is a large entrance hall and behind it a top-lit staircase hall with cast-iron balustrades. In the 1860s wing there is a high-ceilinged ballroom with elaborate plasterwork, and other rooms have the remains of good cornices and other decoration.

|

| Hanworth Park House: the house in its current derelict condition. |

In 1917, the grounds of the house became a private aerodrome belonging to J.A. Whitehead, and from 1929 this became the London Air Park, which operated until the Second World War. The house was used as a clubhouse, and some of the present decoration may be neo-Georgian work of c.1935. After the War, the grounds were acquired by the local Urban District Council, and opened as a public park in 1959. The house became an old people's home, and has been empty since this closed in 1992. Proposals for conversion to hotel use came to nothing, but more recently there has been a scheme for the house to be adapted for a museum and other community purposes, with enabling development in the grounds.

Descent: Sir John Crosby (d. 1475); to son, Sir John Crosby (d. 1501); to kinsman Peter Christmas, whose trustees sold c.1507 to Crown; given 1532 to Anne Boleyn (d. 1536) and reverted to Crown; given 1544 to Queen Catherine Parr (d. 1548) when it again reverted to Crown; granted in 1558 for life to Anne Stanhope (c.1510-87), widow of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset; freehold sold to tenant, Sir Francis Cottington (c.1587-1652), 1st bt. and 1st Baron Cottington, whose estates were assigned in 1649 to the regicide John Bradshaw, but recovered in 1660 by his nephew, Charles Cottington; sold 1670 to Sir Thomas Chambers (d. 1692); to son, Thomas Chambers (d. 1736); to daughter Mary (d. 1783), wife of Lord Vere Beauclerk (d. 1781), 1st Baron Vere of Hanworth; to son, Aubrey Beauclerk (1740-1802), 2nd Lord Vere of Hanworth, and later 5th Duke of St. Albans; to son, Aubrey Beauclerk (1765-1815), 6th Duke of St. Albans; to widow, Grace Louisa (1777-1816), Duchess of St. Albans; to sister, Mrs. Laura Dalrymple; to niece, Lady Ailesbury, who sold 1840 to the tenant, Henry Perkins; to Algernon Perkins (d. by 1866); sold to Messrs. Pain & Bretell, solicitors, of Chertsey; who sold c.1873 to Alfred Lafone (c.1821-1911); to son, Alfred William Lafone (d. 1938) who sold sold 1929 to National Flying Services/London Air Park; sold? 1935 to National Flying Syndicate; sold c.1956 to Feltham Urban District Council; transferred 1965 to London Borough of Hounslow... Gary Cottle.

Redbourne Hall, Lincolnshire

A substantial but now much subdivided house, the architectural history of which is not well understood, although there is a fair amount of archival evidence on which to draw. The main body of the building consists of two wings at at right-angles to each other. The earlier, aligned roughly east-west, was apparently originally of two storeys, and has seven windows on the ground and first floors. Panelled interiors suggest this block dates from the 1720s or 1730s, and it was probably built for the Carter family after they sold Kinmel Hall (Denbighs.) in 1729, paid off their considerable debts, and made Redbourne their seat. Two carved relief panels now in the outbuildings to the east, depicting Harvest and Autumn, one of which is dated 1734, may be an indication of the date of the building. This part of the house was given a third storey, with only three windows on the courtyard front, in the late 18th or early 19th century, and a lower two-storey kitchen wing was added to its right in c.1820-30.

|

Redbourne Hall: view of the house from the entrance court in 1958. The three-storey block in the centre is the oldest part of the house.

Image: Historic England. |

|

| Redbourne Hall: view of the west front of the house by J.C. Nattes, 1795. Image: Lincolnshire Archives. |

The west wing consisted of a miscellaneous collection of buildings when Nattes drew his view of the house in 1795. By then it had acquired a single-storey curved bow at the right hand end, which can probably be identified with payments for the construction of a bow window in 1770. It was built in brick and later raised to provide a bow on the first-floor room as well, an alteration which is marked in a change in the colour of the brickwork. In 1778 a carver and gilder called Hudson and a joiner called Bunning were paid for work, but what they did is unclear.

|

| Redbourne Hall: the west wing in 1958. Image: Historic England. |

The range was apparently rebuilt, except for the bow window, in the first quarter of the 19th century, and is now of two storeys, which are almost the same height as the three storeys of the main block; it contains three principal rooms on the ground floor. The range is constructed of squared limestone blocks, but the window surrounds are of red brick; an unappealing effect which may imply the range was originally stuccoed or painted. The range has seven bays, the right hand two of which are masked by the earlier bow window. The ground-floor drawing room behind the bow now has plasterwork decoration of the 1820s. At the far end of the room, opposite the bow window, is a semicircular recess, which in 1958 still contained a mahogany serving buffet, which must have been made for the room and implies that this was originally the dining room. Another room, which was in use as the dining room in 1958 but was probably originally the drawing room, has a Rococo plasterwork ceiling which must have been preserved when the wing was rebuilt. A terminus ante quem for the completion of the early 19th century refitting is provided by payments made for furnishings to John Lovitt of Hull and for chimney pieces to John Earle in 1827-8. A new staircase hall was built to the south of the west range in the later 19th century.

|

| Redbourne Hall: entrance lodges and gateway, attributed to John Carr. Image: Brian Westlake. Some rights reserved. |

In 1773 and again in 1784 John Carr of York was paid for making plans for the Rev. Robert Carter-Thelwall, but nothing about the house suggests his hand. What is very much in his style is the castellated boundary wall and gateway built at the entrance to the estate in 1776, and indeed the RIBA has a drawing attributed to Carr which shows a similar gateway, albeit with Batty Langley-ish quatrefoils and arched recesses in place of the cross-shaped arrow slits and carved panels that decorate the Redbourne gateway. There is also a range of Gothick outbuildings at the back of the hall which could have been built to Carr's design. The carriage house of 1854, now partly incorporated into the house, is built of yellow brick and has a large lunette window, like a miniature Kings Cross station. The west wing now forms a single dwelling, but the rest of the house and outbuildings are now divided into flats and small houses.

Descent: sold 1613 to Oliver and Thomas Style... Sir Thomas Style; to four daughters, who in 1708 obtained an Act of Parliament for the division of their inheritance, with Redbourne passing to Elizabeth, wife of Thomas Carter (d. by 1703) of Kinmel (Denbighs); to son, William Carter; to son, Thomas Carter; to brother, Rev. Robert Carter-Thelwall (d. 1788); to daughter, Charlotte (1769-97), first wife of William Beauclerk (1766-1825), 8th Duke of St. Albans; to son, William Aubrey de Vere Beauclerk (1801-49), 9th Duke of St. Albans; to son, Rt. Hon. William Amelius Aubrey de Vere Beauclerk (1840-98), 10th Duke of St. Albans; to son, Charles Victor Albert Aubrey de Vere Beauclerk (1870-1934), 11th Duke of St. Albans; sold 1917... Sir Arthur Colegate; requisitioned for RAF 1939...

Newtown Anner, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary

|

| Newtown Anner: the house in the late 19th century. Image: Tipperary Museum of Hidden History. |

A nine bay late Georgian house, with a two storey centre of three bays and taller, three-storey wings to either side that break slightly forward. The date usually associated with the house is 1829, but this may refer only to the addition of the wings, reputedly built for Sir Ralph Bernal (later Bernal Osborne) MP. The central doorcase has engaged columns and a large semi-circular fanlight over the door and sidelights. On the left hand end of the house is a two-storey bow window. Inside, there is a fine saloon. The grounds are enhanced by a shell grotto, well-preserved walled garden and a ruined temple.

Descent: Clonmel Corporation sold 1774 to ?? Osborne...Catherine Isabella Osborne (1819-80), wife of Ralph Bernal Osborne (1808-82); to younger daughter, Grace (1848-1926), wife of Rt. Hon. William Amelius Aubrey de Vere Beauclerk (1840-98), 10th Duke of St. Albans; to younger son, Osborne de Vere Beauclerk (1874-1964), 12th Duke of St. Albans.; given 1958 to Col. John Eric Durnford Silcock (1913-2005); sold c.2000..Nigel Cathcart.

Principal sources

Burke's Peerage and Baronetage, 2003, pp. 3459-64; VCH Hampshire, vol. 4, 1911, pp. 109-12; M. Girouard, 'Acrobatic Gothic', Country Life, 31 December 1970, pp. 1282-86; P. Beauclerk Dewar & D. Adamson, The house of Nell Gwyn, 1974; H.M. Colvin et al., The history of the King's Works, vol. 5, 1660-1782, 1976, pp. 323-40; S. Gillott, 'Bestwood: a Sherwood Forest Park in the 17th century', Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire, vol. 89, 1985, pp. 57-74; Sir N. Pevsner, J. Harris & N. Antram, The buildings of England: Lincolnshire, 2nd edn., 1989, pp. 608-09; J. Roberts, Royal Landscape, 1997, pp. 163-70; B. Wragg, The life and works of John Carr, 2000, pp. 196-97; D. Crook, 'The foundation of Bestwood Lodge', Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire, vol. 106, 2002, pp. 71-72; D.L. Roberts, Lincolnshire Houses, 2018, pp. 228, 388; C. Hartwell, Sir N. Pevsner & E. Williamson, The buildings of England: Nottinghamshire, 3rd edn., 2020, pp. 128-29.

Location of archives

Beauclerk family, Dukes of St. Albans: Redbourne estate deeds and papers, 17th-20th cents [Lincolnshire Archives RED and 2RED]; Bestwood Park estate records, 1785-1841 [Nottingham University Library, BP]; Hanworth estate deeds and papers, 17th-20th cents, legal and family papers [London Metropolitan Archives, 1005; LMA/4245; Acc/0918]

George Beauclerk, 3rd Duke of St. Albans: Glassenbury Park estate and household papers, 18th century [Kent Archives Centre, U410]

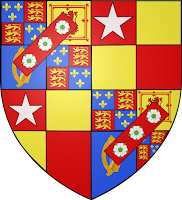

Coat of arms

Quarterly, 1st and 4th grand quarters, the arms of Charles II (1st and 4th, France and England quarterly, 2nd Scotland, 3rd, Ireland) all over a sinister baton gules, charged with three roses argent, barbed and seeded proper; 2nd and 3rd, quarterly, gules and or, in the first quarter a mullet argent.

Can you help?

- Does anyone know of an image of any kind of the medieval hunting lodge at Bestwood that was pulled down in 1860, or of the 'naval castle' built by Lord Amelius Beauclerk in the late 18th century?

- If anyone can offer further information or corrections to any part of this article I should be most grateful. I am always particularly pleased to hear from current owners or the descendants of families associated with a property who can supply information from their own research or personal knowledge for inclusion.

Revision and acknowledgements

This post was first published 25 March 2022 and updated 27 April 2022.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment if you have any additional information or corrections to offer, or if you are able to help with additional images of the people or buildings in this post.